Interview Date | May 12, 2020

JILL: Welcome to the DisTopia podcast, where we look at disability from the inside out. [peaceful music fades in] My name is Jill Vyn, and I’m the cohost of this podcast with my friend and colleague, Chris Smit.

What you are listening to now is the first of two interrelated components of our My Dearest Friends project, both of which have been generously underwritten by the Ford Foundation. The My Dearest Friends podcast, which is produced by DisTopia, is a series of recorded conversations with disabled people about their individual experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the personal, cultural, and political alterations it has triggered. These informal conversations give our guests the opportunity to share personal experiences of sheltering in place and to engage in conversations around deeper questions raised about the value of disabled people, the core values of the disability culture, as well as our hopes, fears, and strategies for living an authentic and pride-filled disabled life.

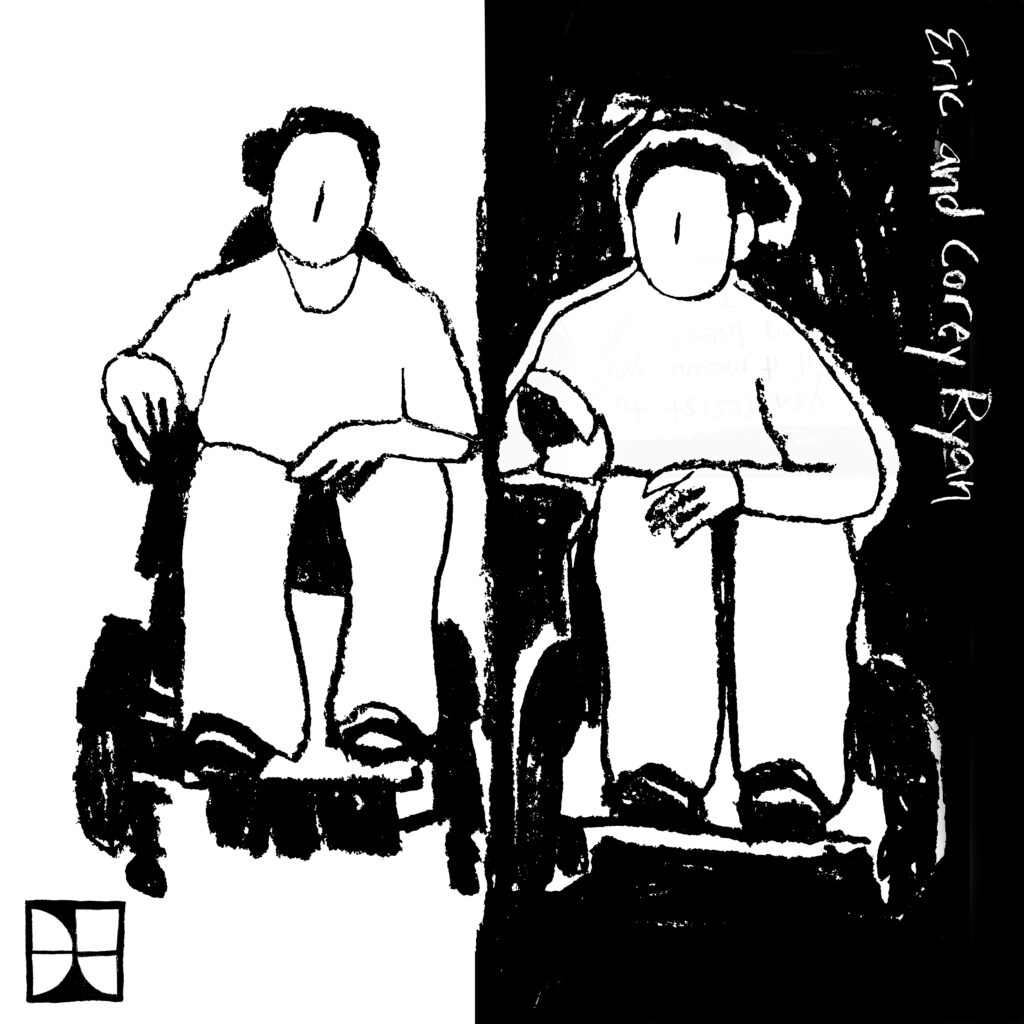

The second component of the My Dearest Friends project is created in partnership with disabled artist Oaklee Thiele, who is creating black and white illustrations that represent our collective response to our new and uncertain realities as a disabled community. Designed as an open invitation to the disabled community around the world, we invite all of you to participate. More information can be found on Instagram @MyDearestFriendsProject, Facebook, and on our website, DisArtNow.org.

As is true for many of you, our desire for this project is to share our experiences as a disabled community, to disrupt ableist beliefs, to celebrate a culture whose lived experience of disability necessitates flexibility and creativity, and to validate disabled voices and perspectives in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

[peaceful music slowly fades away]

ERIC: So, what am I talking about? Are we just starting off? [chuckles]

COREY: Go, Eric. If you wanna just introduce yourself.

ERIC: All right.

[dance music break]

ERIC: Hey, everybody. What’s going on? Thank you, Jill and Chris, for having us on. My name is Eric. Obviously, I’m here with my brother, Corey. And what’s up, bro?

COREY: What up, yep. I’m Corey. I also am his twin. Thank you, everyone, for having us on, and we really appreciate it.

ERIC: We’re pretty much just hosts of Cripple Streets Podcast. I think we started like two years ago, three years ago, and we have problems having to keep shit going. So, I would say the first year, we would do like an episode, and then just not do another one for like three months. Then finally, somebody was like, “You know, if you kept it going, you might have something because you’re pretty fucking funny, you and you brother.” And we’d also talk about just shit that crippled people and disabled people deal with on a daily basis. So, that’s what, yeah, it started.

COREY: Yeah, yeah. I’ll just tell a little bit about ourselves. We’re both 31 years old. Holy shit. Yeah, we’re 31 years old.

ERIC: [chuckles] Dude, you know what it took me yesterday? I was looking up because I was getting ready for this podcast. I’m like, how fucking old am I? I’m like, all right: 1988, carry the 1. All right. I’m 31. [laughs] I was like Jesus, it took me like 10 minutes to figure out how old I was!

COREY: Yep. We both have muscular dystrophy, Duchenne’s with characteristics— Uh, no. Congenital with characteristics of Duchenne’s, whatever the fuck that means.

ERIC: When you say you got Duchenne’s, you get more shit from the government, which we need, so.

COREY: That’s it. So, we just write down that we have Duchenne’s ‘cause we get mad shit for that: like nursing and money.

ERIC: Which we would need to live on our own, so it’s not like we’re just doing it for the fun of it. This isn’t awesome, but yeah, we do it. [laughs]

COREY: We both work. We’re both debt collectors, so you may hear my voice telling you, “You owe money.” So, that’s always nice.

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: But you won’t be able to understand me. I’ll be like, “You owe money.” And it’ll be like, “What?” “You owe money.” “What?” This is the life we live.

ERIC: [laughs] And other than that, I mean, I do the same shit. I’m also a debt collector. Other than that, we just really, with this quarantine going on, don’t do shit! Trying not to die and get sneezed on, that’s about it. [laughs]

COREY: Yep. Don’t sneeze on me, and I don’t wanna die. That’s pretty much my life for the last 60, 51 days? I don’t remember how long I’ve been here.

ERIC: [chuckles] Don’t know what day it is.

CHRIS: [chuckles] I did debt collection too, and I’m wondering if there’s like this crippled thing that makes us good debt collectors.

ERIC: Oh, give us a minute. Let me tell you what it is.

CHRIS: Thank you.

ERIC: I’m gonna help you right now.

CHRIS: OK.

ERIC: The situation with being a debt collector: no one wants to see your face.

COREY: Yeah, you’re sad to look at, usually.

ERIC: We’re sad to look at. So, they say, “Listen. We’re gonna put you on a phone so no one has to look at you.” The problem is I have a speech impediment.

COREY: And it’s strong.

ERIC: It’s strong. So, I’ve actually had someone tell me, “Sir, do you think the best place for you is on the phone?”

COREY: [chuckles]

ERIC: I said, “No.”

COREY: No, I don’t!

ERIC: “I don’t think that’s the best place for me.”

COREY: But this is all they’ll let me do!

ERIC: These are the only people that will hire me. So, here we are. Pay your bill, and that’s the problem.

COREY and ERIC: [chuckle]

JILL: Has that been your experience?

COREY: Yes.

ERIC: Absolutely, yes. We actually both have our Bachelor’s degrees in Accounting. Let’s be real. Corey was unmotivated before he had a fiancé.

COREY: Totally unmotivated.

ERIC: He was happy. He’s like, “Dude, they expect very little from us. Why do we not just take it?” I was like, “You know, we spent thousands of dollars on a degree. Let’s try to get a fine job.”

COREY: Yeah, but we don’t have to pay it back. We’re in wheelchairs.

[dance music break]

ERIC: [laughs] So, I must’ve gone on, honestly, I would say 100 interviews. And this is the best story to give an example of what we would deal with, both of us. But I get a phone call from some CPA saying, “Oh, I got your résumé. You seem like a great candidate. I’d love to have an interview with you.” Me, not thinking because this is like one of my first interviews, I didn’t think, hey, are you handicapped accessible? So, I’m like, “Awesome.” I waited two weeks. I pull up to the door, and I see a flight of stairs. So, I called him, and I’m like, “Hey, man. I’m downstairs.” He’s like, “All right. I’ll come right down.” He comes down. He looks at me. I look at him, and I’m like, now this is where you say something. And he’s like, “Um…so, you wanna do the interview?” I was like, “Well, is there another way to get in? ‘Cause if not, I’m gonna need you to draw me a map on how I’m supposed to get upstairs.” And he’s like, “Oh, um, I didn’t even think of that.” He’s like, “How about this? Go home, and maybe we can do a phone interview. I’ll call you back tomorrow.” I was like, “Not a problem. I’ll hear from you tomorrow.” That was over five years ago, and I’m still waiting for that—

COREY: [chuckles]

ERIC: —I’m still waiting for that phone call. So, I don’t think he’s calling back. Corey tells me to lose hope. I’m still keeping the phone near me, but I don’t think it’s gonna happen.

CHRIS: Corey, have you had experiences like that too, then?

COREY: I mean, again, he’s not lying to you. I was very unmotivated. He was like, “All right. Listen. We gotta do something.” So, I’m like, I’ll try and do this telecommunication job. So, I applied. I actually got hired. I show up, and they look at me. I look at them, and they’re like, “You didn’t tell us you were in a wheelchair.” I’m like, “I didn’t think I had to.” So, we go into the back room. The room is really tight, and they’re like, “I don’t think you’re gonna fit back here.”

ERIC: [chuckles]

COREY: I’m like, “No! We can make it work.” So, I try and like shove my chair in the room, but it’s not gonna work. I’m like, “Is there any way we can do this in the front?” They’re like, “Listen. We’re gonna set this up for you. We’re gonna set up your own office. Just give me a call back tomorrow.” I said, “What time? What time do I have to call you back?” “10:00 am.” I said, “Perfect.” So, I wake up at like 8:00 in the morning. I’m fucking pumped. I’m like, my first job. My dad’s not gonna give me shit anymore.

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: I’m like, perfect. I call them at like 9:58. No answer. I call them at like 11:00. No answer. 12:00, “Hey, listen. It’s Corey Ryan,” blah, blah, blah. “Oh, yeah. We’re gonna give you a call back in a week. Wait for our call.” “OK, perfect.” Same fucking situation: I’m still waiting for a call that’s not coming.

We tell people. We don’t tell people. It is what it is. People don’t hire crippled people.

ERIC: [laughs] I have one other story that’s even worse than that, now that we’re on the subject of having trouble getting hired. I even joined a temp agency.

COREY: [laughs] Oh, yeah.

ERIC: And they’re like, “Oh, we’re gonna find you job.” I was like, “All right. Good luck, ‘cause I couldn’t do it.” So, [chuckles] I was like, “If you find me a job, you’re the best fucking temp agency ever.” I get an email a month later: “Hey, we got you a place at Stoneybrook University.” I’m like, “Dope.” They’re like, “You’re gonna be working in the mail room where we send out equipment to science department.” I was like, “I don’t give a shit what I’m doing as long as I’m getting paid.”

COREY: And I’m sitting there, laughing. I’m like, “Listen. There’s no way you’re doing this, but I would love to see how this happens.”

ERIC: [laughs] So, I get there. The boss immediately looks at me, and I get that weird feeling like oh, someone didn’t warn her. So, [chuckles] we shake hands, and she goes, “This is what I need you to do. And then at the end of the day, I need you to file all of these papers.” Now, let’s be real. I can’t really open anything either, so filing was gonna be an issue. But she didn’t tell me that I needed find a way to file it. So, at the end of the day, I said, “All right. Where do you need me to put these?” ‘Cause in my mind, I’m gonna have my 24-hour nurse—who literally just sat outside, and I’ve known her since I was 12, so she doesn’t care—I was just gonna have her come in, pretty much be my hands. I would instruct her on where to put it as long as the boss had no problem. But she didn’t even give me an opportunity to discuss it. She goes, “Oh, forget about it. Don’t worry about filing.” I’m like, “Are you sure?” I was like, “You told me in the beginning of the day that this is part of the job.” She says, “Oh, don’t worry about it,” but not like it was a problem. She said, “No, don’t worry about it. Not a big deal. No problem.”

I don’t know if you guys remember there was a snowstorm. Well, we had it in New York, like five years ago, where if you lived 20 minutes from your house, it took you five hours to get home. So, I get a text message the next day from my nurse, and she goes, “Hey, your friend just got here because it’s snowing, and they wanna get home before you have a problem getting in your house.” I tell my boss, and they’re like, “Yeah, no problem. Don’t worry about it.” I get an email two days later from the temp agency saying, “We got an email from your employer stating that the office wasn’t accessible, and you couldn’t get around and you couldn’t reach the filing cabinet.” I responded like, “What are you talking about? It’s an open floorplan, and the filing cabinets are against the wall.” And they said, “Well, they said that one of the issues was you couldn’t file.” I was like, “You didn’t ask me to file! You told me it wasn’t an issue!” So, a much shorter version of a longer story is she pretty much came up to the conclusion that I wouldn’t be able to file, so she just took, instead of her talking to me, she handed it off to the temp agency and was like, “Yeah, we don’t want you.”

COREY: But to be fair to her, I mean again, to be fair to her, look at you. I would assume—

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: —you could not file.

ERIC: This guy has a problem taking a sip of coffee. I don’t see filing in his future.

COREY: All she had to do was watch you eat lunch one time, and you’re not filing anything.

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: But she should’ve asked ‘cause then she would’ve realized what the plan was!

[dance music break]

CHRIS: And you guys have obviously an approach to life that is completely beautifully painted with humor. I’m really curious—maybe Jill, you are too—but is it funny at the moment, or is it funny a year later? ‘Cause I often have this like, for me, it’s usually funny in the moment. But there’s some stories that I’m like—

JILL: Uh, no!

CHRIS: —I’m not laughing!

JILL: No, no, no. I’m gonna call you out on that.

CHRIS: [laughs] No, no, no. But I’m saying that there’s a lot of situations where—

JILL: OK, OK.

CHRIS: OK, go. Yeah, yeah.

JILL: We have been in France.

CHRIS: [laughs]

JILL: And we were trying to get on the train. It was not funny in the moment.

CHRIS: [sighs]

JILL: And you were not laughing at all!

ERIC: [laughs]

CHRIS: I know! I know! But—

JILL: Now we could laugh about it!

CHRIS: Right, right, yeah. So, I would say most things are like that, right? Where it like bad, and you’re like, “Fuck my life. What the heck?”

COREY: [laughs]

CHRIS: And then you know, depending on, how long did it take us to laugh, Jill, about that? A year?

JILL: I don’t know if we’ve laughed about it yet.

ALL: [laugh]

ERIC: You’re laughing now!

JILL: We’re laughing now. No, it’s a bit dehumanizing.

CHRIS: Oh, yeah!

JILL: At the time, I’m observing, and it looks dehumanizing when people are making decisions for you.

CHRIS: Yeah.

JILL: Or you are not able to engage in the world in the way that you know you can creatively make it happen.

ERIC: Yeah. I’m not gonna lie to you. I agree with what you’re saying, and I feel like it’s important to have people the way that you think, where it is dehumanizing. I agree with you. I’m not disagreeing at all. At the same time, for somebody who goes through it, you can definitely call it out as dehumanizing. But there is definitely humor behind it, only, well, I wouldn’t say humor. But you try to find the funny ‘cause the irony is, it happens all the time. I think that’s the funny part, not the fact that it’s actually happening.

JILL: Well, you don’t have a choice but laugh about it.

ERIC: Right, right, exactly. And it should change. I’m not saying we shouldn’t try to change it all the time. But it’s just like, oh, it’s happening again. That’s hilarious. Not it’s actually funny, but I hear what you’re saying.

JILL: There’s another one where, Chris, it was BS where—well, I guess we’re with you guys—it was bullshit—

ERIC: [laughs]

JILL: —with United Airlines. And—

ERIC: Fuck United Airlines. [chuckles]

JILL: —there was a whole issue about your chair and on and on. And I get it. In the moment, it’s terrible, and then afterwards, you’re talking with your friends who have been there and experienced it. But it doesn’t take away the fact that these things shouldn’t be happening.

COREY: My fiancée’s parents live in Michigan, so I go to Michigan with her. And it happened the last time. On our way home, my chair, so, we gave it to the I guess whoever puts it underneath the plane. I guess someone must’ve taken apart a Permobil before—

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: —‘cause they took the back off, but I didn’t give it to them like that. So, they took it upon themselves to take the back of my chair off, unscrew it. I didn’t give it to them like that, so I didn’t know that that’s what they did. So, when it got brought back to me, it was pretty much apart. So, needless to say, I’m sure you can tell now, I’m not afraid to speak my mind. So, there was a few curse words thrown around. But I do think that as far as my experience with things that really shouldn’t be, I find humor in a lotta things. That time, it wasn’t really that funny.

ERIC: At all.

COREY: But after, I mean, you do have to laugh about it, or you’ll just become—

ERIC: Unless you’re the one picking him up—

COREY: Right.

ERIC: —and you have to wait outside the damn airport for four hours! I’m like, what? How long does it take to get off a fucking airplane, Corey? And he’s like, “They took my chair apart.” I was like, “Then stab them and take it!”

COREY: [chuckles]

ERIC: “Because I don’t wanna be here.”

COREY: Yeah. Again, laughing, though sometimes, it’s not funny, it is the only way to— ‘Cause what’s the other alternative? I mean, I wasn’t gonna get pissed at that moment. I could yell. I could scream. But really, it wasn’t gonna—

ERIC: And you did write a letter. It’s not like you didn’t take action later on trying to correct the problem.

COREY: Oh, of course. But at that moment, I have two options. I can either laugh about it, or I can become super upset and depressed about it. And I always choose to laugh about it because if not, I’ll just fucking wallow in, yeah, whatever. I’m not saying that no one has the right to. I just choose not to do that.

CHRIS: No, and I think that’s a choice that a lotta disabled people have to make pretty early on in their life, right?

COREY: Yeah.

CHRIS: Like whether or not these things that we deal with, are they going to be things that we grow from and move through, are they gonna be things that completely destroy us? Now, the problem with that is that there are certain things that are a lot harder to handle, right?

COREY: Yes.

CHRIS: Like for me, when I was a kid, it was hard for me in high school when my friends would just grab a car and go and do whatever they wanna do, right? So, like, ugh! That was really, that was hard, right?

COREY: Absolutely.

CHRIS: But it didn’t destroy me, right, because I was able to talk about it with my disabled brother and my friends and be like, “Hey, assholes. Don’t leave me home! Don’t leave me home,” you know? You guys have those things too, right, I’m sure.

ERIC: We were very, very, very blessed, lucky enough where we have a older brother who we’re only two years apart from him. He’s 34, and he has no disability, nothing like that.

COREY: He’s fat as fuck, but—

ERIC: He’s fat as fuck, but being fat isn’t a disability. That’s just laziness. So, [chuckles] but he’s actually probably one of the best people I know. Up until the age of 16, we were close but not with his friends. He had his own group of friends. But then once we turned 18, my aunt, one of my aunts used to be a snowbird, so she would go to Florida from New York on the winter months. And she would have my brother, my older brother watch her condo for three to four months at a time. So, I would say every weekend, he would have his friends over, and then he would take me and Corey—and this is before 24-hour nursing—he would take me and Corey in our, he built the ramp. We would get into the condo, him and his friends. I mean, I have zero problems with being—

COREY: Yeah, all of his friends have seen my dick.

ERIC: Yeah. I have no problem being naked in front of people ‘cause I mean, we just, it just was. I had no problem, like, “Hey, man. Can you help me take a piss? I really gotta go.” So, we were very lucky in regards to our friends. They didn’t treat us any differently at all.

COREY: And we understand. I went to Henry Viscardi School, which is all disabled kids. So, I know not everyone’s that lucky. But I mean, all my friends, they’ve always talked shit. We talked shit about being disabled. We were just, not to say normalized, but we were just, it was just something else to talk shit about. You know, they helped us use the bathroom. Our mom and dad were big on always take care of each other. So, my big brother was always like, “Yeah, they’re coming wherever I’m going.” It didn’t really matter. So, I’ve never experienced being left out. Maybe between 16 and 18, that was more of like a age gap than really the disabled thing.

ERIC: Yeah. I’ll give you a perfect example. We went to a house party once with my brother and two of his friends, and there was a girl there—this is like beginning of college—who wanted to mess around in one of the bedrooms. One of my brother’s friends literally said, “Oh, that’s not a problem,” threw me over his shoulder, carried me up two flights of stairs, and put me in the bedroom and was like, “Call me when you need me,” and left. That was the kinda friends we had. So, we were very, very lucky. They did not, yeah, they had no problem with helping us or doing anything like that, which might have played in the reason [chuckles] we are the way we are.

COREY: We’re so fucked up! [laughs]

ERIC: [laughs]

[dance music break]

CHRIS: Talk about school. Did you guys go to school? Were you mainstreamed? Did you go with other disabled kids? How did that work out?

COREY: We both went to the Henry Viscardi School, which is in Albertson, New York. So, Henry Viscardi was a man that was born without his legs, so he made a school for physically-challenged kids. Me and Eric went there from Kindergarten—they had pre-K, but I didn’t go there for pre-K—we went from Kindergarten to 12th grade.

ERIC: They had PT, OT, a swimming pool. We would have a Physical Therapist go around the school and put students for like 30 minutes in supine boards, and then obviously, later on in the early 2000s, they would put the students in standers where you would sit down, and they’d strap you in and stand the chair up. They had a bathroom with three attendants for the men’s room, three attendants for the female room. And if you needed help, they would help you use the bathroom. They had speech therapy—

COREY: Physical therapy, occupational therapy.

ERIC: The gym classes were all adapted, so like we played hockey, baseball, basketball, football. There were rules. Like in our football game, we had levels of crippled-ness. If you were like me, who couldn’t really, I could catch the ball on occasion. If my gym teacher threw the football at you, and it hit you in the body, you could keep moving until someone tagged you. If it hit you in the wheelchair, it counted as a catch, but you had to stop right there. So, just as an idea, there were different rules to everything. So, socially, it wasn’t as good, I think, as if we would’ve went to a quote-unquote “mainstream” school. But at the same time, it did allow you to see how other people with disabilities may’ve handled their own situation. I think they’re doing a better job now of preparing people for after Henry Viscardi, but my biggest gripe with them was they did not prepare you for being a disabled person in the real world.

COREY: That’s how I feel about school and education. But as far as socially, I agree to a certain extent. I still have friends from when I was in 1st grade.

ERIC: Yeah.

COREY: So, I wouldn’t necessarily say socially they didn’t prepare you. But as far as schooling, my English teacher was great. But other than that, they didn’t really prepare you for college or things like that or how the real world—

ERIC: But you also have to remember: me and you are coming from, like with our brother, Sean, and hanging out with our own friends, which might be why we still have friends like we do today. There were kids there who, if you put them in a room with anybody who wasn’t disabled, just like somebody who isn’t disabled acts towards somebody with a disability, they don’t know how to act.

COREY: You’re right. Absolutely, yeah.

ERIC: I don’t mean they can’t keep a friend. I just mean it inhibits, it’s like they see somebody who isn’t quote-unquote “like them,” and which is— I mean, we started our podcast to help people see a handicapped person and just talk to them like a person sitting down. And I think it’s the same goes for someone who never interacts with quote-unquote “normal” people. It’s like they’re just standing up. That’s the only difference.

COREY: Yeah. Yeah, I agree. I would agree with that standpoint.

ERIC: Don’t get me wrong. I have my gripes, but I couldn’t speak more highly of that school.

COREY: Very good for people with disabilities. I highly agree.

JILL: You know, it sounds like in helping to prepare for discrimination, ableism, and being able to recognize that and how to manage that. And it also sounds like what you were saying is preparing for productivity.

COREY: Yeah.

JILL: Right? You’ve seen Crip Camp?

COREY: Yes, yes. I loved it.

ERIC: I love that, yes. We actually, that’s gonna be our next project.

COREY: Yeah.

ERIC: On our podcast, we’re gonna discuss Crip Camp and our experience in camp.

COREY: Yeah. Shit got crazy. I’m gonna have to dial it down a little bit, but yes. [laughs]

CHRIS: Yeah, I have experiences at camp that I have not made public as well. And I had MD camp—muscular dystrophy camp—which, I think maybe you guys went to. And when I was young, there were no rules, man.

COREY: Yes, there were no rules.

CHRIS: No, there’s still, yeah, but they—

ERIC: I don’t know about still, but when I was—I’m 31 now—when I was 16, 17, 18—

COREY: That’s when everything happened, yeah.

CHRIS: Yeah. No rules whatsoever. Now they’ve made it so like you can’t go if you’re over 18 or 19 or something like that, right?

COREY: It used to be 24, and then they made it 21. And then I think you’re right. I think they made it like 19 or 18, which still doesn’t make sense ‘cause some of the counselors are 18.

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: So, it’s like you’re putting two 18-year-olds, well, 20 18-year-olds if you count counselor to camper ratio. Only difference is they’re in a wheelchair.

ERIC: I will tell you: I feel like your [chuckles] your opinion of women might be slightly more handicapped-accessible.

COREY: [laughs]

ERIC: They’re much more willing to get to know you. [laughs]

COREY: Well, yeah get to—

ERIC: They’re more liberal. They’re more liberal is what I’ll say.

ERIC and COREY: [chuckle]

CHRIS: I remember when I went, there was no age limit, and it was really—

COREY: That’s dope.

CHRIS: —the only time that I was around disabled adults, you know, at all.

COREY: Yeah.

ERIC: Yeah.

CHRIS: And so, I had these guys with muscular dystrophy who were, at the time, in their 30s, and I was like 16. And my parents dropped me off for a week! It’s like, “Here. Have a weekend.” It’s like these college kids who were the attendants there.

COREY: [laughs] They’re like, “Chris. This is a pussy.”

CHRIS: Yeah! Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah! Oh, no, but they’re more like, “Chris, we’re gonna give you the best week of your life.

COREY: Yeah. [laughs]

CHRIS: But for me, I grew up in a school where I was mainstreamed, and I had physical therapy, and I had OT in a special room. So, I didn’t have a lot of disabled friends, man.

ERIC: Go to your special room!

CHRIS: I had a special room! Yeah, I had a special room, yeah.

ERIC: That’s so fucked up. That’s hilarious. [laughs]

CHRIS: Yeah. But it’s really affected my own understanding of my own disability.

ERIC: Yeah, yeah.

CHRIS: So, like in some ways, I didn’t really understand being disabled until my late 20s, you know?

COREY: That’s wild.

CHRIS: Yeah.

COREY: I do have to say: it’s like beating a dead horse, but my parents were really good about making me understand what was gonna happen to me or what could happen to me—‘cause no one can say what will happen to you—but what could happen to you based on what your disability is. So, I mean, in school, they made us do book reports on what our disability was. But my parents from—

ERIC: Like, fuck that. [laughs]

COREY: —from a very young age, like, “Listen. We’re gonna do research together. This is what you can expect, and this is just what it is. This is what your life may entail, not what it will entail, but it may entail. And it is what it is. So, I have a very practical view on things like that.

[dance music break]

And I can’t stop thinking about what Jill said. I mean, I definitely understand ableism. Like, it’s not a fake thing. We talked about it not last podcast, but the podcast before. I’m right in the middle. Yes, there are people, they just don’t understand what we go through day to day, but I also think that as a disabled community—again, I’m young, so I haven’t lived through your everyday, what older people have—but I have a real problem calling able-bodied people ableist, if you will. I think there’s a difference between ignorance and chosen ignorance. If you choose not to research, then you’re an asshole. But if you just don’t know, then I have a real problem saying like, “Oh, you’re choosing not to do this.” Some people just don’t know. They don’t get it.

ERIC: And I’m not judging anyone who speaks this way.

COREY: Of course.

ERIC: But me and Corey talk about this all the time. The quickest way to get somebody to not listen to what you’re saying is to start calling them names or telling them that they’re doing something that they should be, like they’re the ones in the wrong. Where really, I think you solve more problems by saying, “This is why we need it this way. This is what I’ve gone through my entire life.” And try to have them put themselves in your shoes instead of saying—I’m not accusing you of this, but I’m saying I’ve seen other people say—“Oh, you ableist piece of shit.” I’m like, well, they’re really gonna listen to you now, you know what I mean?

COREY: [chuckles]

ERIC: And again, I understand the want to do it ‘cause I’m not—

COREY: Or the anger. I’ve gotten angry before.

ERIC: I’m not gonna lie to you. In my head, I might’ve said those things. But as I get older, I realize usually—and again, sometimes it doesn’t matter if you call somebody the worst thing in the book; they’re just not gonna change—but I would say 95% of the time, if you can explain to somebody and get them to put themselves in your shoes, usually, they’re willing to change. I’ll give you an example. We went to a place in Patchogue which is a town on Long Island. The name of the restaurant is Gallo. Now, all of the restaurants there are accessible, but all the bathrooms are super tiny. So, it was our first time there, and I’m like, I gotta use the bathroom. So, I went over to the bartender, and she was like, “Yeah, gimme a second.” The owner came up to me and was like, “Follow me.” We go in the back. I’m like, “Where are you taking me?” He allowed Corey and myself to use their upstairs catering room, the banquet room, and he had a elevator, which blew my fucking mind ‘cause it’s a restaurant. And I was like, “Dude! Do you know you’re like the only guy in Patchogue, maybe Long Island that has an elevator to go upstairs?” And he’s like, “Dude, I want everybody to come enjoy my restaurant.” I mean, we go there all the time now before the quarantine.

COREY: Yeah, we’re actually friends with the owner now, but.

ERIC: Yeah, I’m good friends with the owner now. He texts us all the time, lets us know when he’s gonna have parties and what not, to get there like an hour before. But the reason for the story is he then went around, talking to all the owners in Patchogue to try to make—even if it’s not an elevator—to try to make their restaurants much more accessible. So much so that the brand new restaurant that got built two summers ago also put in an elevator. I don’t wanna say it was just for me and Corey. That’s not why. But to make any patron be able to enjoy it. So, I feel like if I would’ve been like—

COREY: “Hey, I’m gonna sue you because I can.”

ERIC: —if we would’ve went through all of them like, “Oh, you’re a piece of shit. How could you not have an elevator.” He went around and was like, “Listen. This is why you want it. You’re making people’s lives better.” I think us and mostly him achieved a lot more that way as well. Just another way of thinking.

JILL: Well, for sure. We believe that relationships have power in making change and that our mission is to help societies move from awareness to understanding to belonging. So, we don’t come across and say, “Oh,”—

COREY: No.

JILL: —we don’t call it out except when it’s blatant.

COREY: Right.

JILL: And there are times when it is blatant, and there’s times when people, I guess we would—I don’t know, Chris, if you would agree or not—should take time to explore their own biases.

ERIC: Absolutely.

CHRIS: Yeah, and there’s ways in which I see Cripple Streets Podcast as your invitation into the world of disability and your way of saying, “I’m not gonna be a dick and say you’re ableist, but I am gonna talk about my life. And so, if you could take a minute and listen,” right? I mean, is that a fair assessment.

COREY: Very fair.

ERIC: Pretty accurate. Yeah, it’s pretty close. That’d be the best way to explain it. And again, if you take a second and listen, you might be like, man, that’s a shitty situation. If I’m a bartender or if I’m an owner, if I’m this, how can I make sure that my patrons don’t deal with something like that? That’s the, honestly, not the only goal, but that would be one of, that would be a nice thing to hear that that’s taking place, for me. I don’t know how Corey feels, but.

COREY: No, I feel the same way. I mean, me and you’ve discussed this. The main reason we did this is for things like that. Don’t get me wrong. Some of it’s comic relief. None of it’s fake. All of it’s fucking true.

ERIC: Yeah, we don’t make it up. It’s not like…. [laughs]

COREY: It’s just our way of seeing things in the world, not saying that seeing things—

ERIC: Any other way is not correct.

COREY: —any other way is incorrect. But you know, we try and give a little bit more of a comic welcome, like hey, this is what we grow through. This is what people like this go through. Let’s try and—

ERIC: Build a bridge instead of say, “You don’t understand me.”

COREY: It goes both ways. I don’t want people to think like, oh, it’s on us to ask for acceptance. There’s people that are like, oh, people are out there just suing people ‘cause they’re not ADA compliant. Well, fuck that. You’re supposed to be ADA compliant.

ERIC: [laughs]

COREY: But I also don’t think if someone isn’t, your initial reaction should be, “Hey, here’s a 30-day notice. If you don’t get it fixed, I’m suing you.” How about, “Hey, this is why I wanna come to your place,” and depending on their reaction, can see how we resolve this situation, as an example.

[dance music break]

JILL: So, we’ve been talking to a lot of people over the last month or so, and common things being shared are value, valuing people in the disabled community, paying attention. People have talked about how they’ve asked for accommodations, or people other than you have talked about discrimination in the workforce. And so, there’s a mix of people’s reactions from hope to what’s people’s awareness with COVID-19 to anger to ugh, it’s just gonna be more of the same. We’re just hearing different reactions to what’s happening with protests, what’s happening with the government, what’s happening. I mean, you know, there’s just lots of opinions out there, and I’m curious what your reactions are.

COREY: I have to be honest with you. As far as the COVID-19 in New York—I don’t really get political, but I have no problem doing it—I’m not a big fan of Cuomo as an overall governor.

ERIC: Politician, yeah.

COREY: Politician. But I think he’s done wonders for New York. I think he’s really taken the whole COVID-19 thing seriously. I am not afraid to say it: I’m not a Donald Trump fan. I do think people pick and choose, not regularly but sometimes, pick and choose dumb shit he says, ‘cause he’s just stupid, than shit that actually affects us, which I think we should get mad about, shit that actually affects us than just dumb shit he says. But overall, I don’t think we’ve handled it as well as we can. Just in my own community, I’ve seen people take walks without masks, mostly older people. I think they just don’t understand. But just people that don’t give a shit. I just don’t understand it. I’m like, listen. It could mean life or death for me. Put on a fucking mask!

CHRIS: We’re dealing with a governor who has one plan for a re-opening, and a lot of people in our state in Michigan are really upset about that. And so, there’s been all these protests, and there’s been some pretty nasty things said and thought about disabled people during that. Have you watched any of those reactions to get back and to quit with the sheltering in place laws and all that?

ERIC: I have. I’m not gonna lie to you. As a disabled person who can get, I joke, but I can literally get sneezed on and possibly get COVID-19, I struggle with it. Because that part of me is 1,000% for any stay-at-home law, obviously. And also, because most of my care and what allows me to live the life that I do is usually favored if you vote liberal or Democratic. But personally, I’m just gonna be honest, if I wasn’t a wheelchair suer, I wouldn’t be Republican, but I’d probably be more Libertarian-leaning only because I feel like when you start making rules by the government, you open up a really weird door where now, depending on who’s in office at the time, that style of government will tell you what you can and can’t do. Now, do I think we need to be more mindful of people like myself, like you, like Corey who can literally get very sick if we get sneezed on? Absolutely. I think there’s a common ground, not where you’re picketing outside with no masks and, “Fuck you! I wanna go out!” It’s like, dude, you haven’t looked like you left the couch in two years, and now you wanna go outside because someone tells you, you can’t?

But also, I don’t think it’s right for people to say you’re gonna get $10,000 fines because I’m lucky enough, even though I’m in a wheelchair, I’m working from home. I’m able to pay my rent, I can pay my bills, and I have food in the fridge. I’m not a single mom, single dad, or a family with three children at home, working. I have zero income. I’m desperate. I don’t know how I would feel at that time. So, I feel like people are very quick to judge and say, “These guys are crazy!” I think that there has to be some kind of common ground. I don’t know what that is. I’m not smart enough. [chuckles] I wouldn’t pretend to say I have the answers, but I try to have at least empathy for people who are angry on the other side. I don’t know what it’s like.

COREY: I agree.

ERIC: Yeah. I don’t know what it’s like to have children. I have no idea what it’s like to look at my bank account, see $30 and am I eating, or is the remainder of my family eating today? So, I get some anger.

COREY: I see it the same way because, like he said, I’m working from home. I have food in my fridge and clothes on my back. I think there’s, especially in the media—and I’m not one to say, “It’s the media’s fault!”—but I do think the medias are showing you two sides of the spectrum. They’re showing you the crazy right that are like no masks, COVID-19’s fake, fuck everybody, let’s go back to work. I also think they’re showing you the crazy left that’s like, all the ones on the right are fucking murderers and crazy people and science deniers. I do think that there is a fine line in the middle. I do think there are people that are just trying to provide for their family. We all don’t know what’s going on, and they’re just nervous ‘cause they don’t see how they’re gonna go back to work.

Now, I do have to say, as a disabled person, I’ve kept close contact with Michigan law, and especially ‘cause my fiancée’s from Michigan. And I think there’s a lot of misinformation from both the left and the right. ‘Cause I know someone that thought that she could be arrested for growing plants in her backyard, which is not an accurate statement. But if you watch Fox news, you could be arrested for being in your backyard. So, I think we have to be careful where are we getting our information, but also, we have to understand there are people struggling out there. Yes, I have an underlying condition, but there are people that are worried about where their next meal’s gonna come from, how they’re gonna feed their children. So, I don’t think it’s as easy as oh, everyone should stay home, or everyone should go out. I do think conversation’s the biggest part of how we’re gonna get through it.

[dance music break]

CHRIS: One of the things that we haven’t asked you about yet is the decision to be publicly living disabled life on YouTube, right, and in a podcast. What did it take to make that decision? And do you think about it that way? Maybe you don’t even think about it that way, but.

ERIC: I can’t speak for Corey, me personally, I was always into podcasts, I would say, for the last 10 years. And also, more of like comic relief podcasts. Even though it is serious, Joe Rogan has a podcast. My favorite comedian, Tom Segura, and his wife has a podcast called Your Mom’s House, which is hilarious, that’s not serious at all. [chuckles] But I have no problem really sharing my life. I mean, I think it might come also from, and we could also touch on disabled life anyway, as you know or you may know, we don’t have a lot of privacy in regards to— People think, oh, they live by themselves. It doesn’t mean I have as much privacy as you would think. I have a nurse— And this is nothing against my nurses. I love all of them. They’ve actually all been my nurses for over 20 years. But I have no privacy. If I wanna do something, at least one other person knows about it. So, I feel like I also didn’t really have a problem with sharing my life because it’s shared anyway. [chuckles] Even if it’s as miniscule as one person, after 30 years, well, then 28 years of having that be the constant, it didn’t really bother me at all.

But also, I do know—and I’m not sharing anything that I don’t think Corey wouldn’t want me to share—I don’t have to worry about anybody else who I share information about because mostly, it’s about myself. And if it’s not, it’s about stories that has to do with from years ago or people not, no one directly. Where Corey has a partner now, so I think he may be slightly more mindful of things that he wants to share and doesn’t wanna share. Which isn’t my place to speak on, but I think it’s probably the only difference.

COREY: I would totally agree. When we started the podcast, I was single. I didn’t give a fuck. I said what I wanted when I wanted about any situation I wanted. Now, even though it’s only one or two subjects, there are things that I have to take into account that it’s not just about me anymore. It’s about my fiancée’s not disabled. So, my life has never been 100% private ever. Like Eric said, either there was one person that knew about it or my parents or whatever. So, now that I have to try and separate privacy as far as I can get with privacy as far as my and me fiancée can get, there are obstacles, if you will. But as far as creating the podcast’s, I’ve never had a super-private life anyway, so maybe my thought was fuck it. Everyone knows it anyway.

ERIC: [chuckles]

COREY: What’s one person or a million people, 50 people? Whatever it is, whoever sees it, whatever. I didn’t really care.

ERIC: And if it breaks down that wall of people, next time someone sees somebody in a wheelchair could say, “Hey, man, what’s going on?” instead of staring and being afraid to talk to somebody. That’s, honestly, I don’t know about Corey, but that was my main goal. Literally, we’re just sitting down. That’s the only difference.

COREY: Absolutely. Yeah. It was pretty much just to make people realize, hey, you can just go up, and I’d rather people ask me questions than this. Now, I’ve had disabled friends that say, “Why is that my—” Listen. People have questions, in my opinion.

ERIC: You’re not the norm. I mean, I hate to say it. In regards to, and I don’t mean it how people are like, “Oh, you’re not normal,” no. But it’s more rare to see—

COREY: It’s all statistics, people. You’re not the norm.

ERIC: If I saw somebody walk in my apartment missing an arm and a jaw, I’m gonna have some questions. It’s not unfair of me to be like, “What happened?” [laughs]

JILL: I would say that not everyone is willing to be as vulnerable and open as you are. And I appreciate that about both of you and the work that you’re doing because it does normalize your experiences and probably helps your listeners as well.

ERIC: And we didn’t just get here. I don’t want anybody who’s listening to be misled that this happened overnight. This is constantly pushing barriers. Another example: my dad and my mom—mostly my dad but also my mom—

COREY: My dad is just savage.

ERIC: [chuckles] I love him. My dad’s probably one of the greatest people I know.

COREY: He made me the man I am today.

ERIC: But I mean, he didn’t hold any punches. I mean, I’m gonna be honest with you. I don’t know. I think he might disagree with the verbiage that he used back then, but back then, I’d be 10 years old, and he’d be like, “You’re crippled. You’re not an invalid.” Like you’re not somebody who can’t do anything. What the fuck are you doing? And my mom, another example. My brother, my older brother, had chores. He would take out the garbage. He would mow the lawn. My mom would take me outta my chair, put me on the floor, and say, “Dust the bottom of the table.” I’m like, “There’s no dust down here.” She goes, “It’s not about the dust. Start dusting.” [laughs] So, shit like that. I think that’s very, very important.

And again, we’re very lucky. I mean, this is more of a serious subject, but both of my parents are still together. They stayed. Let’s not pretend like disability isn’t—

COREY: Yeah, absolutely. I have conversations with a lotta my friends, and I’m like, “Listen,” whoever they are, “You don’t get mad at your dad.” I say, “Listen. My dad stayed.” I mean, it is what it is. I’ve had disabled friends, and usually, the mom stays, the dad goes. That’s just the way it is. My dad may’ve been a hard ass and said some shit that you may not like hearing to disabled people, but he stayed. So, I mean, I gotta give the man credit ‘cause it is what it is.

ERIC: And he didn’t talk to me any differently than he would’ve talked to my older brother.

COREY: Exactly.

ERIC: He’s like, “I’m not gonna pull punches because you’re in a wheelchair. Because I promise you, everybody outside the house won’t pull any punches either.”

COREY: Absolutely. [chuckles]

[dance music plays through next few sentences]

CHRIS: Good stuff. Thank you, guys. Thank you for spending some time with us.

ERIC: Yeah, absolutely. It was a great time. Thank you for having us.

COREY: Anytime!

JILL: Thanks for listening. Be well, keep your distance, send us your comments, questions, and your submissions for Oaklee Thiele to hello@DisArtNow.org. Please make sure to follow the My Dearest Friends project on Instagram, Facebook, and DisArtNow.org. And thanks again to the Ford Foundation for their support of this work and to cat enthusiast Cheryl Green for the transcription of this podcast episode.

Music: “Cream Dream” by Crash Symbols (Source: FreeMusicArchive.org. Licensed under a Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License.)